A Democratic win on Nov. 3 could bring with it the repeal of at least two key elements of the Trump tax cuts, which could boost High Yield’s appeal relative to stocks.

By Bruce H. Monrad, Chairman, Northeast Investors Trust | October 2020

Click here to read a PDF of this article.

While it doesn’t always matter to the markets who’s in the White House—as Wall Street has thrived under Republican and Democratic presidents alike—High Yield investors may want to pay attention to the Nov. 3 election results, especially if Joe Biden wins amid a so-called Blue Wave.

Should Biden become president and the Democrats seize control of the Senate, it’s safe to assume taxes will rise, which investors typically loathe. Yet the taxes that Biden is talking about lifting could actually make High Yield a competitive alternative to stocks for risk investors in the coming years.

Blame the Deficit

If most current polls are accurate, Biden could be a few months away from stepping into the Oval Office, where he will inherit a staggering $3.3 trillion budget deficit. The federal government was already on track for a record-setting shortfall before the pandemic pushed the consumer economy into a recession. The passage of the $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act has only compounded that.

Moreover, should the outgoing Congress fail to pass a second round of Covid relief after the election, you can expect an incoming Democratic administration and Congress to push for more aid in the early stages of a Biden presidency. And that could add another $2 trillion or more to the deficit.

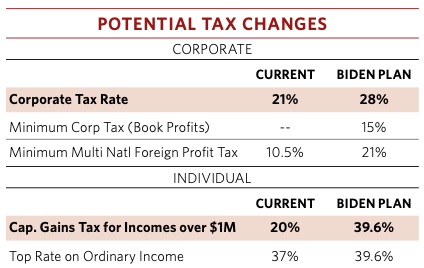

To address the deficit, Biden is already on record as saying he intends to repeal several elements of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (the Trump tax cuts), including raising the corporate tax rate—which Trump slashed from 35% to 21%—back up to 28%. The Biden plan also re-establishes a minimum corporate tax (based on book profits) and doubles the tax on foreign earnings of U.S. firms with overseas subsidiaries, according to the Tax Foundation.

Corporate Taxes: Advantage High Yield

While rising taxes are a concern for investors across the board, an increase in corporate taxes this time is likely to hurt stocks more than bonds.

Why? For starters, many investors believe that after a spectacular rebound after the March market crash, equities are now “priced for perfection.” The price/ earnings ratio for the S&P 500 index of U.S. stocks, based on 10 years of averaged (or “normalized”) earnings, has climbed to nearly 32, which means equities are nearly twice as expensive as their long-term average. Also, because the price that investors are willing to pay for stocks is directly based on future earnings, higher corporate taxes could weigh on stock prices in the coming years.

To be sure, High Yield securities could also be hurt by rising taxes, as some High Yield issuers might see their profit growth slow. But bond investors look at earnings not so much as a tool for pricing securities but to assess whether companies are financially strong enough to meet future obligations. In this light, the higher taxes High Yield issuers may have to pay are offset by record low interest rates that are expected to remain low for several years. The effective yield that non-investment grade firms are paying has fallen to 5.5%, down from more than 13% two decades ago.

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve is doing something it has never done before: The central bank is openly purchasing fixed income securities including High Yield debt through ETFs to maintain liquidity in the credit markets. The central bank is also lending directly to companies through special lending facilities established during the coronavirus economic shutdowns. In effect, the central bank is agreeing to serve as a backstop of sorts for bond issuers who may be hurt by the global pandemic.

For High Yield investors worried about defaults, this is welcome news. The bond-rating agency Fitch forecasts that U.S. High Yield defaults will hover between 5% and 6% by the end of 2021. That’s well below the 14% High Yield default rate at the peak of the global financial crisis a decade ago and the 16% rate during the 2000-2002 tech wreck.

Capital Gains: Advantage High Yield

In addition to corporate taxes, Biden has also called for raising taxes on capital gains and dividends for high earners. Should this come to pass, the move could marginally reduce investor interest in stocks while increasing the relative appeal of bonds and High Yield.

Biden’s campaign has proposed boosting the top rate on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends from 20% today up to 39.6% for households making $1 million or more. If Biden gets his way and the top income tax rate also reverts to pre-Trump tax cut levels, bond income and stock appreciation would be on equal tax footing (at least for high earners) for the first time since 1990. It would also bring taxes on bond income and qualified stock dividends in alignment for the first time since 2003.

While investors are often warned not to let taxes drive their decision making—”don’t let the tax tail wag the investment dog”—the recent gap between lower capital gains (and dividends) and higher ordinary income taxes made equities a default choice for risk investors.

No More Tax Excuses

Why does this matter? As we previously discussed, we believe there’s a case to be made for shifting a portion of one’s equity allocation into High Yield now. Over the long run, historical data would suggest that High Yield can provide investors with equity-like returns with more downside protection. And over shorter periods of time, High Yield has outperformed stocks at key moments, sometimes for several years at a stretch.

This happened after the bursting of the Internet bubble in 2000 and following the global financial crisis starting in 2007, when High Yield outpaced stocks for seven years. It’s very possible that we could be in store for another period of High Yield outperformance post pandemic. This is especially true if rising corporate and capital gains taxes encourage investors to look at High Yield as an alternative to equities.

Even if High Yield does not outperform, shifting a modest portion of one’s equity allocation—even just 10%—to high yield can offer investors a surprising diversification benefit. For example, since 1987, a portfolio consisting of 70% U.S. stocks and 30% investment-grade bonds produced annualized returns of 8.7%. A similar portfolio that moves 10% of that equity stake into High Yield would have gained nearly the same—8.4% annually—but with 10% less volatility.

Tax-aware equity investors might frown on such a move in the current tax environment. But one has to wonder if that will still be the case after Nov. 3.

Click here to read a PDF of our article.

Bruce H. Monrad is chairman and portfolio manager of Northeast Investors Trust (ticker: NTHEX), a no-load, high-yield fixed income fund whose primary objective is the production of income. Bruce is among the longest-tenured bond fund managers, having run Northeast Investors Trust for more than 30 years. He received his A.B. from Harvard College and his M.B.A. from Harvard Business School.

CONTACT: 1-800-225-6704 (M-F 9:00am – 4:45pm EDT); bmonrad@northeastinvestors.com

Join our email list to get the latest informed news and commentary from Northeast Investors Trust.

DISCLAIMER: From time to time a Trustee or an employee of Northeast Investors Trust may express views regarding a particular company, security, industry or market sector. The views expressed by any such person are the views of only that individual as of the time expressed and do not necessarily represent the views of the Trust or any other person in the Northeast Investors Trust organization. Any such views are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions, and Northeast Investors Trust disclaims any responsibility to update such views. These views may not be relied on as investment advice and, because investment decisions for Northeast Investors Trust are based on numerous factors, may not be relied on as an indication of trading intent on behalf of the Trust.