High Yield: An Alternative to Stocks for Investors Seeking Downside Protection

Investors unsure of the April market rebound can hedge their bets through high yield bonds, which capture most of the upside of equities—but with much less volatility.

By Bruce H. Monrad, Chairman, Northeast Investors Trust

The coronavirus-sparked market crash that began in late February with a swift 34% decline in the S&P 500 index was followed by an equally speedy 30% rebound by late April, leading some investors to wonder if the bear market might be over as quickly as it began.

Then again, some of the biggest surges in stock prices over the past century took place in 1929, 1931, 1933, 1937, 2001, and 2008, all of which were in the midst of bear markets. In other words, there’s a decent chance the April rebound could be a classic bear market rally that falls short of the escape velocity needed to propel equities out of their slump.

This poses a quandary: How can investors position their portfolios in case this rally is for real while also guarding against the chance that it isn’t? Traditionally, worried investors have tried to hedge their bets by shifting to defensive equities such as consumer staples. But the sector, which has traditionally traded at a discount to the S&P 500, owing to its slower growth, now trades at a price/earnings ratio of 19.2, based on projected profits over the next 12 months, according to FactSet. That’s a slight premium to the S&P 500’s forward P/E of 19.1.

Missing, so far, has been a discussion on the role that high yield bonds can play as a potential replacement for a portion of one’s stock allocation.

High Yield as a Stock Proxy

Swapping out a modest weighting of one’s equity portfolio with a form of fixed income may seem unconventional, but high yield is in many ways more closely linked with equities than with high-grade bonds. For the past 30 years, high yield has had a 0.63 correlation with U.S. large-cap stocks (1.0 implies perfect synchronicity), which is much higher than its relationship with investment-grade bonds (0.31) or 10-Year Treasuries (0.01), according to Portfolio Visualizer, an investment analytic software platform.

High Yield’s Risk Advantage

To be sure, high yield bonds haven’t delivered quite the returns that U.S. stocks have generated. Since 1990, high yield has posted annualized gains of 6.9%, vs. 9% for equities. But over shorter stretches — for instance, from the start of the tech wreck in March 2000 through December 2005, and from the start of the financial crisis in October 2007 through the end of 2012 — high yield has occasionally outpaced equities.

And over the past 30 years, high yield has delivered 77% of the gains of the S&P 500 with only around half the volatility. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, given high yield’s relatively short durations and the greater bankruptcy protection it offers investors over stocks.

Even better: In years when stocks have fallen, high yield has typically lost less. When the S&P 500 index sank 37% in 2008, the average high yield bond fund lost a more modest 26%. And when stocks dropped 22% in 2002 — the final year of the bear market after the bursting of the dotcom bubble — high yield funds posted losses of less than 2%, on average.

High Yield’s Diversification Effect

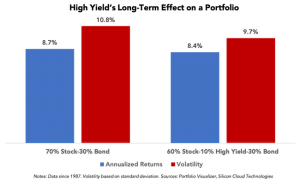

Shifting a modest portion of one’s equities — even just 10% — to high yield can offer investors a diversification benefit. For example, consider two strategies: Portfolio A consists of 70% U.S. stocks and 30% investment-grade bonds, while Portfolio B is 60% U.S. stocks, 10% high yield, and 30% bonds.

Since 1987, Portfolio A produced annualized gains of 8.7% with a standard deviation, a common measure of volatility, of 10.8%. Portfolio B gained 8.4% annually — in other words, 97% of the gains of A — but with 10% less volatility by shifting a sliver of equities into high yield.

What’s more, B outperformed A in every recent major downturn, including the 2007-2009 financial crisis, 2000-2002 bear market, and the 1987 crash.

High Yield is Less Frothy Than Stocks

Of course, there are no guarantees that swapping out some of one’s equity stake for high yield will always lead to more downside protection. However, the fact that stocks remain at historically high valuations, even after the market sell-off earlier this year, speaks to the underlying risks that remain in equities.

The last two periods of high yield outperformance over stocks — in the years following the tech wreck in 2000 and the global financial crisis in 2007 — had one thing in common: frothy stock valuations that made equities much more susceptible to major losses. At the end of April, the S&P 500’s forward P/E of 19.1 was 27% higher than its average over the past 10 years.

Why? While stock prices have fallen, profit forecasts for companies in the S&P 500 have dropped even more, owing to the shutdown of large swaths of the global economy to slow the spread of COVID-19. Earnings for the broad market are now expected to shrink 15.2% in 2020, according to FactSet.

By contrast, high yield isn’t nearly as richly priced. The spread between yields for high yield bonds and 10-year Treasuries stood at 7.8 percentage points at the end of April, which was considerably wider than the 3.9-point average gap over the past three years.

High Yield’s Income Advantage

By its nature, high yield enjoys an income advantage over Treasuries and stock dividends. But this is only amplified during periods of low interest rates, such as the environment we’re in now. In March, the Federal Reserve cut its target for the federal funds rate down to 0%-0.25% while yields on 10-year Treasuries sank to 0.6% at the end of April. By contrast, high yield bonds are paying out around 8%, on average.

Meanwhile, investors who have been attempting to supplement their income through dividend-paying stocks have been equally frustrated by recent developments. Rising stock prices over the past several years have weighed on the dividend yield of the S&P 500. Then the economic shock amid this pandemic has forced companies to conserve cash, making matters worse. Roughly two dozen companies, including Royal Dutch Shell, General Motors, Delta Airlines, and Boeing, have recently cut or suspended their dividend payments amid heightened economic uncertainties. The trend is likely to continue. Goldman Sachs forecasts that in 2020, the total amount of corporate dividends paid will be slashed by 25%.

As investors seek out income in an environment where it’s getting harder to find, attention is likely to again refocus on high yield, where payouts aren’t nearly as good as they were a decade ago — but at least yields are still high on a relative basis.

Download a PDF version of our article.

CONTACT: 1-800-225-6704 (M-F 9:00am – 4:45pm EDT); bmonrad@northeastinvestors.com

Join our email list to get the latest informed news and commentary from Northeast Investors Trust.

DISCLAIMER: From time to time a Trustee or an employee of Northeast Investors Trust may express views regarding a particular company, security, industry or market sector. The views expressed by any such person are the views of only that individual as of the time expressed and do not necessarily represent the views of the Trust or any other person in the Northeast Investors Trust organization. Any such views are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions, and Northeast Investors Trust disclaims any responsibility to update such views. These views may not be relied on as investment advice and, because investment decisions for Northeast Investors Trust are based on numerous factors, may not be relied on as an indication of trading intent on behalf of the Trust.